Real de Dolores Mine Safeguard Project

The Real de Dolores Mine Safeguard Project is located about eight miles south of the village of Cerrillos, in Santa Fe County, New Mexico. The project site consisted of eight shafts, two adits, two pits, and two open stopes, all of which are dangerous to the public at large. The project area was on private land in the Ortiz Mine Grant in R7E and R8E, T13N (sections not assigned).

This project won OSM’s National Abandoned Mine Reclamation Award in 2007.

The project was significant for a couple of reasons. First, it was Program’s first time it had used polyurethane foam to safeguard mine openings. Second, the Ortiz Mine has a rich historical record going back to 1822. The history includes the oldest gold lode mine in the West, the first railroad in New Mexico and the work of Thomas Edison on a gold separation mill. Preserving the history while safeguarding human health of visitors and colonies of bats living in the mines were important aspects to this project.

This project involved the following work:

- Backfilling of one adit, four shafts, two pits and one open stope using mine waste and other nearby material (at some sites, borrow shall be taken only from designated areas).

- Construction of a cable net closure over one of the above shafts following backfilling.

- Construction of bat cupolas with corrugated steel pipe risers, polyurethane foam plugs and concrete collars at two shafts.

- Construction of polyurethane foam plugs at one shaft and one open stope, including backfilling of both with imported lightweight fill material.

- Construction of welded wire fences at one adit trench and one collapsed shaft.

- Placement of straw wattles on slopes indicated on the plans and as directed by the Project Manager and planting of seedlings.

- Closing of temporary construction access trails.

- Incorporation of compost and fertilizer into all areas disturbed by construction and as otherwise specified and seeding and mulching as specified.

The contractor was St. Cloud Mining Company based in Truth or Consequences, NM.

Year Completed: 2003

Cost: $154,913.00

Project Engineer: John Kretzmann, P.E.

Project Manager: Raymond Rodarte

HISTORICAL PHOTOS

PROJECT AREA BEFORE CONSTRUCTION

Benton Mine

Old Ortiz Mine (Tunia Shaft)

English Mine

Old Ortiz Mine (McPhee Shaft)

PROJECT AREA AFTER CONSTRUCTION

When Nuevo Mexico was part of New Spain, now Mexico, visitors from other countries were not welcome. Zebulon Pike’s experience in his expedition of 1807 was typical – he and his men were arrested by Spanish authorities in what is now southern Colorado, and jailed in Santa Fe and Chihuahua before his release. In 1821, when Mexico gained independence from Spain, it opened its borders to traders and travelers and the Santa Fe Trail was started.

To pay for the influx of manufactured goods from the United States and Europe, gold became the most desired means of payment and, by the mid-1820s, led to a gold rush 30 miles south of Santa Fe in the Ortiz Mountains, about 25 years before the California gold rush.

Most of the early gold mining in the Ortiz Mountains was placer mining. Adjacent to the project was an area of extensive placer mining. Miners dug down to the bedrock surface where gold tended to concentrate in the alluvial fans at the base of the mountain. Due to the lack of surface water in the area, most placer mining took place in winter, when snow was melted to aid in separation of gold from the sands and gravels.

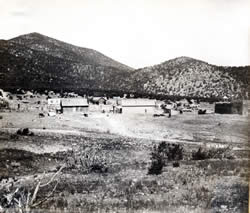

The gold rush helped to establish a mining town nearby, Real de Dolores (also known as Dolores), the earliest known gold mine camp in the West. The placers on the north side of the Ortiz Mountains continued to produce gold throughout the 1830s, before moving to the south side of the Ortiz Mountains.

As early as 1831, a gold lode mine, the Santa Nino mine, was in operation in the Ortiz Mountains. The Santa Nino is the earliest gold lode mine in the Western United States with a known location. In later years the workings along the Ortiz vein were combined into one mine – the Old Ortiz Mine.

In 1846, in part because of the interest in the mineral wealth of the southwest, the United States invaded Mexico and the US Army occupied Santa Fe. In 1847, a stamp mill was constructed in Dolores, the first such mill in the Rocky Mountains. The mill was nearly a mile and a half from the mine and mules hauled the ore from the mine to the mill.

In 1854, the New Mexico Mining Company (NMMC), the first mining corporation in New Mexico, formed to expand the Old Ortiz Mine, sinking several new shafts. In an effort to expedite the movement of ore from the mine to the stamp mill in Dolores, the Mining Company constructed the first rail line in New Mexico in 1868. This rail took ore from the mine in rail cars one and one-third miles to the mill, but proved to be much more costly than originally estimated and the mine closed a couple of years afterwards. Significant production began again in 1880 at the Old Ortiz mine with the coming of the railroad to New Mexico and continued into the early 1900s.

The perennial lack of water sources in the Ortiz led the NMMC to make an agreement with Thomas Edison to design and build an experimental industrial-scale dry placer plant, completed in 1900. The mill only operated for five months, the moisture level in the placer deposits were too high and caused the gold particles to bond to other rock and pass into the tailings.

The long history of mining in the Ortiz Mountain has left an archaeological legacy on the land, including a flywheel and foundations from a stamp mill at the New Live Oak Mine, remnants of the Ortiz Mine railroad grade, and the remains of an arrastra, a small circular stone ore crusher used by small-claim miners. Recognizing the mining legacy of the area, the New Mexico Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Program began to survey the Ortiz Mountains in the early 1990s, locating eight shafts, two adits, two pits and two open stopes dangerous to the public. Avoidance areas for preservation of historic artifacts were designated.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Gold Fields Corporation worked an open pit mine within a half mile of the Ortiz Mine. After a joint venture between Pegasus Gold Corporation and LAC Minerals in the late 1980s, Pegasus withdrew and LAC Minerals was left with the job of remediation and reclamation of the mine site.

By the time NM AML was entering the design phase in the mid-1990s, LAC Minerals donated 1,350 acres of land, including the Ortiz vein, to the Santa Fe Botanical Garden as part of the settlement of a groundwater pollution lawsuit. The Botanical Garden agreed to conserve and maintain the site and offers educational programming to the public at the Ortiz Mountains Educational Preserve. Recently, the Botanical Garden entered into a management agreement with the County of Santa Fe, transferring ownership of the preserve to the County as part of its open-space program.

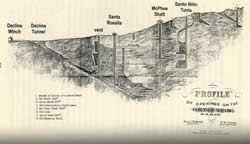

By the 1990s, most of the shafts and the decline tunnel at the Ortiz Mine had either collapsed or been filled by Gold Field during their operations, but the unnamed, possibly oldest, workings at the upper right of this map and Santo Nino/Tunia Shaft and adjacent stope were open. Fill material in the McPhee shaft was subsiding and the shaft was open to a depth of 15 feet.

Two of the openings, however, had occupants that had moved in after mining. Townsend’s big-eared bats were using the underground workings at the Tunia Shaft and at the English Mine shaft, a quarter mile to the north of the Ortiz Mine. The bats were using these mine workings for both summer maternity and winter hibernations sites.

The Tunia Shaft and stope and the English Mine Shaft presented engineering design challenges – the near-surface rock at the openings requiring bat cupolas was weathered and required stabilization to support structures. The stope adjacent to the Tunia shaft intersected the shaft (just beyond the rock bridge in the center of the photos) and had to be sealed for public safety without blocking the shaft.

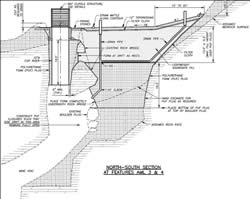

The final design for the stope opening incorporated a polyurethane foam plug 16-feet deep, covered with 12 feet of lightweight scoria fill (to minimize loads on the plug), filter cloth and one foot of soil topdressing. Requiring 100 cubic yards of foam, this is the largest PUF plug designed to date by the NM AML. The Tunia shaft required a 15.5-feet deep foam plug, a six-foot diameter corrugated steel pipe riser, and four feet of scoria fill.

The motif at the Tunia Shaft cupola of diagonal bars meeting at 90 degrees symbolize the meeting and sometimes clashing of the cultures that met at the Old Ortiz mine – the Hispanic settlers of over 200 years of a remote corner of the Spanish Empire and the traders and miners from the young, restless country called the United States. The overall cubic form of the cupola (6.5 feet on each side) recalls the cubic crystalline structure of gold. The lower bars are spaced at four inches clear for the safety of children and the upper horizontal bars at 5.75 inches clear for bat passage.

The subsided McPhee Shaft at the Ortiz Mine was within 50 yards of the visitor’s kiosk for the Educational Preserve. Given concerns about the continuity and stability of the fill in the shaft and to insure long-term public safety, the subsidence was filled to the surface, a cable net anchored to bedrock around the opening (as a secondary safety measure, in case the shaft subsides again), and the net covered with rock both to mark the shaft’s location and for erosion control

As possibly the oldest workings on the site, the unnamed workings at the upper end of the Ortiz Mine site were fenced, as was the highwall at the collapsed decline into the Ortiz Mine workings. Other smaller pits, stopes and adits, most dating back to the 1880s and including one of the two English Mine shafts, were backfilled for public safety.

The foundation for the bat cupola at the English Mine, located on LAC Minerals property, was constructed similarly to that at the Tunia shaft – with a polyurethane foam plug, this time eight feet deep, and a six-foot diameter riser pipe.

The cupola for the English shaft was designed with two sides sloping at 60 degrees above horizontal. This helped to minimize the weight of the prefabricated steel structure, which had to be ferried to the site up a steep, narrow abandoned mining road. Both cupola structures were constructed using weathering structural tubing. AML chose this material for its strength, aesthetics and permanent corrosion protection of the steel.

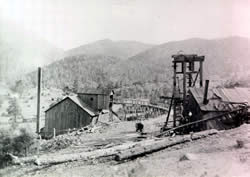

At the Benton Mine, active between the 1880s and 1930s, and located on LAC Minerals property, the timber shaft lining had partially collapsed, creating an unstable debris plug 35 feet below the surface. To ensure a permanent shaft closure, a nine-foot thick PUF plug was placed in bedrock and covered with five feet of lightweight scoria fill, left visible to mark the shaft location. This helped to preserve the mining district’s only remaining headframe structure and the near surface remnants of the timber collar. Since Gold Field had removed the mine waste on three sides of the headframe for reprocessing in the 1980s, fill was borrowed nearby and placed around the structure’s base for stabilization.