Frequently Asked Questions about WIPP

What is WIPP?

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) site is located 26 miles southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico in an area known as Los Medanos (“the dunes”). This area of New Mexico is relatively flat and is used primarily for grazing. Potash mining and oil exploration and production are quite prevalent in the area. Fewer than 50 people live within 10 miles surrounding the WIPP site and only 50,000 live in the entire county.

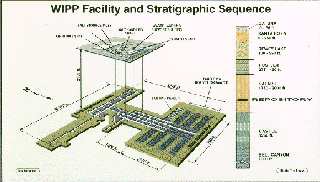

WIPP is essentially a very sophisticated salt mine designed for the permanent disposal of transuranic wastes (or TRU wastes) generated from defense-related activities (i.e., research and development of nuclear weapons). The repository itself is 2,150 feet (655 meters) below the surface of the earth in the Salado Formation. If certified for waste disposal, waste will be placed in tunnels and chambers dug by state-of-the-art mining methods located in a 3,000-foot-thick salt formation at 1,250 feet above sea level and 2,150 feet below the surface.

WHY SALT? In 1956, the National Academy of Sciences recommended salt formations as a suitable medium to permanently dispose of radioactive wastes. The salt formation was selected because of its “plastic” nature — it creeps under pressure. The idea behind disposal in a salt mine relies on the underground pressures to cause the salt to close in on the waste and seal it in the underground rooms, rendering the waste immobile. The site near Carlsbad was selected for exploration in 1974. Excavation began in 1982. Four shafts allow access and ventilation to the mine.

The above-ground complex at the WIPP facility includes a waste handling building where the waste will be unloaded from TRUPACTs and inventoried, inspected and prepared for disposal.

You can find out more about the WIPP facility by contacting the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Carlsbad Area Office.

Aerial Photo of WIPP’s above-ground facilities. Aerial Photo of WIPP’s above-ground facilities.[/caption] |

This graphical representation of the WIPP Facility can be seen at DOE’s WIPP Web site. Click on the picture to go there. This graphical representation of the WIPP Facility can be seen at DOE’s WIPP Web site. Click on the picture to go there.[/caption] |

What is Transuranic Waste?

Primer on Radioactive Waste*

What is radiation? Radiation is energy in the form of high speed particles or electromagnetic waves. It can be ionizing or non-ionizing. Non-ionizing radiation lacks the energy to alter atoms (e.g., visible light and microwaves). Ionizing radiation has enough energy to change normal cellular functioning. Ionizing radiation may cause cells to die or transform into a cancerous cell. Ionizing radiation is categorized by its strength or energy level into three main categories:

What is radiation? Radiation is energy in the form of high speed particles or electromagnetic waves. It can be ionizing or non-ionizing. Non-ionizing radiation lacks the energy to alter atoms (e.g., visible light and microwaves). Ionizing radiation has enough energy to change normal cellular functioning. Ionizing radiation may cause cells to die or transform into a cancerous cell. Ionizing radiation is categorized by its strength or energy level into three main categories:

- Alpha particles, although the most densely ionizing, are the weakest form of ionizing radiation. They can travel a few inches through the air but can be stopped by something as thin as a sheet of paper. This means that cells can be protected or shielded from damage by alpha particles by clothing. Even your skin will protect you from damage from alpha particles. However, if alpha particles are inhaled or ingested or get into a cut on the skin, they can cause damage to cells. As alpha particles decay inside the body, the surrounding cells absorb the radiation.

- Beta particles contain more energy than alpha particles. These particles are able to travel several feet through the air, but can be stopped with denser materials such as wood, glass or aluminum foil.

- Gamma rays are high-energy electromagnetic energy waves and the most penetrating type of radiation. They travel at the speed of light through the air. Cells must be shielded from gamma rays with concrete, lead or steel.

What is a Half-Life? Radioactive elements are unstable and spontaneously decay, causing them to emit radiation. The speed at which radionuclides decay is measured in “half-lives.” A half-life is the time it takes for one-half of the radioactive atoms to decay into another form. Sometimes the form that the atoms decay into are also radioactive elements. After several half-lives only a fraction of the original radionuclides exist. Depending on the type of radionuclide, half-lives range from a few seconds to hundreds of millions and even billions of years. The type of ionizing radiation (i.e., alpha, beta, gamma) is NOT related to an element’s half-life. For example, some alpha emitters, such as Uranium-234, have half-lives of hundreds of thousands of years. The Uranium-238 Decay Chain illustrates this point.

What is a Half-Life? Radioactive elements are unstable and spontaneously decay, causing them to emit radiation. The speed at which radionuclides decay is measured in “half-lives.” A half-life is the time it takes for one-half of the radioactive atoms to decay into another form. Sometimes the form that the atoms decay into are also radioactive elements. After several half-lives only a fraction of the original radionuclides exist. Depending on the type of radionuclide, half-lives range from a few seconds to hundreds of millions and even billions of years. The type of ionizing radiation (i.e., alpha, beta, gamma) is NOT related to an element’s half-life. For example, some alpha emitters, such as Uranium-234, have half-lives of hundreds of thousands of years. The Uranium-238 Decay Chain illustrates this point.

What is Radioactive Waste? Radioactive or nuclear wastes are the wastes that result from nuclear weapons production, nuclear power generation and other uses of nuclear materials. These wastes are usually categorized by their level of radioactivity (i.e., High-Level Waste, Transuranic Wastes, and Low-Level Waste). These waste also can be categorized by source. Defense-related radioactive wastes are those resulting from the research and development of nuclear weapons. Civilian or commercial nuclear wastes are the result of nuclear energy production, radioactive materials used in medical treatments and research and in certain commercial goods.

- High-Level Wastes are very radioactive (gamma emitters). They require heavy shielding and remote handling. High-level wastes include spent (or used) nuclear fuel from nuclear reactors and wastes resulting from reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel. Fuel assemblies in nuclear reactors must be replaced after several years, when they are no longer efficient in producing electricity. Spent nuclear fuel is more radioactive than new fuel. Most spent nuclear fuel in the United States is currently located at nuclear generating plants across the country in pools of water to protect workers from radiation. Spent fuel also can be stored in large concrete casks.

Reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel, which is the chemical separation of plutonium and uranium from other elements, is no longer done in the United States with spent fuel from commercial nuclear reactors. Almost all high-level wastes from reprocessing come from the reprocessing of fuel from weapons production reactors to obtain materials to make nuclear weapons. This waste is primarily in liquid form and can be “vitrified” into a glass or other solid substance.

High-level radioactive waste is stored at nuclear power plants and DOE facilities across the country. DOE’s Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management is charged with identifying and developing a suitable site for deep geologic disposal of this waste. They are currently conducting research to determine the suitability of a site for such disposal at Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Check out DOE’s Yucca Mountain web site and the State of Nevada’s Nuclear Waste Project web site.

- Transuranic (TRU) wastes include laboratory clothing, tools, plastics, rubber gloves, wood, metals, glassware and solidified waste contaminated with man-made radioactive materials including plutonium, americium and neptunium. Some of these wastes, known as “mixed” transuranic waste, also contain hazardous chemical constituents that are regulated under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. (TRU waste that does not contain regulated amounts of hazardous chemicals are called “non-mixed” TRU wastes.) TRU wastes were created in the research, development and fabrication of nuclear weapons. They include all wastes contaminated with radionuclides possessing atomic numbers greater than uranium (which is 92) and half-lives greater than 20 years and are in concentrations greater than 100 nanocuries per gram.

TRU waste is usually classified as either “contact-handled” (CH) or “remote-handled” (RH). CH-TRU emits mostly alpha radiation and therefore does not require heavy lead shielding. The primary radiation hazard posed by this waste is through inhalation or ingestion. Inhalation of certain transuranic materials, such as plutonium, even in very small quantities, could deliver significant internal radiation doses. RH-TRU wastes are primarily gamma emitters; consequently they require heavy shielding and must be handled robotically. RH-TRU present a much more significant external radiation hazard than CH-TRU waste.

Currently most TRU is stored in 55-gallon drums or other containers at DOE facilities across the country. TRU wastes generated prior to 1970 are in shallow burial at these sites. While there is no plan to move currently buried wastes, DOE plans to dispose of some transuranic waste in the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (or WIPP) in southeastern New Mexico. However, by law WIPP will be able to accept only a portion of the TRU waste that currently exists and will be generated in the future.

Find out more about about plutonium from the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research.

- Low-Level Wastes are those radioactive wastes that are not high-level and not transuranic. Most low-level waste (classified by the NRC as A, B or C) has relatively low levels of radioactivity, relatively short half-lives and can be disposed of by shallow burial. Wastes that are “greater than class C” require deep geologic disposal in specially licensed facilities.

* References used to generate this page:

The Nuclear Waste Primer: Handbook for Citizens, Revised Edition, by the League of Women Voters, Published by Lyons & Burford, 1993.

“What is Radiation? How Do We Measure It?” Backgrounder #4, produced by the National Safety Council’s Environmental Health Center, December 12, 1996.

How many shipments of WIPP-bound waste will go through New Mexico?

Dates for shipments are the most recent dates provided by DOE. They are tentative and subject to change as more information becomes available from DOE.

Opening of shipment routes will be phased-in:

Generator Site Initial Shipping Date

Number of Shipping Dates |

||||

| Contact-Handled Beginning 1999 | Remote-Handled Beginning 2003 | Total | ||

| Los Alamos, New Mexico | March 25, 1999 | 1,760 | 111 | 1,871 |

| Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Lab | April 27, 1999 | 9,651 | 255 | 9,906 |

| Rocky Flats, Colorado | June 15, 1999 | 2,261 | 0 | 2,261 |

| Hanford, Washington | July 12, 2000 | 1,806 | 920 | 2,726 |

| Savannah River Site, South Carolina | May 8, 2001 | 1,830 | 0 | 1,830 |

| Mound Laboratory, Ohio | TBD | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| Argonne National Lab-East, Illinois | TBD | 26 | 109 | 135 |

| Lawrence Livermore, California | TBD | 106 | 0 | 106 |

| Nevada Test Site | TBD | 112 | 0 | 112 |

| Oak Ridge, Tennessee | TBD | 124 | 473 | 597 |

| Battelle Columbus Laboratory, Ohio | TBD | 0 | 40 | 40 |

| Energy Technology Engineering Center, Santa Susana, California | TBD | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Totals | 17,706 | 1,914 | 19,620 | |

Dates of first shipment are for contact-handled (CH) wastes only. U.S. DOE projects that remote-handled (RH) waste shipments will commence in January 2003. For an explanation of contact- and remote-handled wastes, look in the Radiation Primer.

Source:

Shipment numbers from the “WIPP Disposal Phase Final SEIS-II,” DOE/EIS-0026-S-2, November 1996, Volume 1, Chapter 5, page 5-13, Proposed Action. Numbers are subject to change.

Information for LANL, INEEL and Rocky Flats initial shipping dates were provided in DOE’s Shipping Notice. Initial shipping dates for all other sites will be promulgated when known.

TBD: To Be Determined.

What roads in New Mexico will WIPP-bound shipments use?

Shipment Routes in New Mexico

The following map identifies the WIPP Shipment Routes designated by the State Highway Commission.

Where will the WIPP-bound waste come from?

PROPOSED WIPP SHIPPING ROUTES

from Major Generator Sites

What laws and regulations must WIPP comply with?

WIPP Transportation Safety Program Laws and Regulations

WIPP Land Withdrawl Act

The guiding legislation for WIPP:

PUBLIC LAW 102-579

THE WASTE ISOLATION PILOT PLANT LAND WITHDRAWAL ACT

as amended by Public Law 104-201 (H.R. 3230, 104th Congress)

EPA Certification

DOE must obtain a permit from EPA (under 40 CFR Part 191) to dispose of the radioactive constituents in the WIPP waste. EPA’s Criteria for the Certification and Re-Certification of the WIPP [Federal Register, February 9, 1996 (Volume 61, Number 28), Pages 5223-5245. From the Federal Register Online via GPO Access (Size 15.8K)] can be accessed on the Internet. DOE submitted a Compliance Certification Application to EPA in October 1996. EPA’s draft certification was issued on October 30, 1997. EPA held hearings and accepted public comment on the draft certification. The final permit was issued in mid-May 1998 and the DOE Secretary notified Congress of their intent to open WIPP.

NMED RCRA Permit

RCRA: Regulations on Hazardous Waste (i.e., chemical waste) The repository must meet requirements of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) for the hazardous constituents in the WIPP waste by submitting a “Part B” permit application to the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) which has been delegated RCRA authority by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

DOE submitted its final RCRA Part B application to NMED in April 1996. NMED reviewed the application and issued a draft permit on May 15, 1998, which was available for public comment through August 15, 1998 (see more on the announcement of draft permit). On November 13, 1998, NMED issued a revised draft permit and a notice of public hearings (see more on the notice of the revised draft and public hearing). Public hearings were held and the Secretary of the New Mexico Environment Department issued a final permit on October 27, 1999. This permit will become effective on November 26, 1999. Final RCRA Part B Permit.

The WIPP Land Withdrawal Act contains a very stringent standard regarding the release of radioactive materials to the accessible environment. Message to 12,000 A.D. provides some perspective on how to prevent future societies from breaching the site. The information contained at this site is all about warning future generations to avoid drilling into the WIPP site. This is important since some of the TRU waste remains radioactive for tens-of-thousands of years.

Radiactive and Hazardous Materials Act

The Radioactive and Hazardous Materials Act [Section 74-4A-2 through 74-4A-14 NMSA 1978] authorizes the Radioactive Waste Consultation Task Force and specifies its duties and responsibilities.

What is the history of WIPP?

WIPP Chronology

The following summary is a chronological listing of key events and decisions relating to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), a mined geologic repository in southeastern New Mexico intended for the permanent disposal of defense transuranic wastes. It is a federal project being developed by the U.S. Department of Energy.

1955: The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) asks a committee of the National Research Council to examine the issue of permanent disposal of radioactive wastes. The committee subsequently concludes that “…the most promising method of disposal of high-level wastes at the present time seems to be in salt deposits.” [National Research Council, 1957, The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land, Washington D.C.: National Academy Press]

1957: The AEC sponsors several years of research (1957-1961) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee on phenomena associated with the disposal of radioactive waste in salt.

1962: The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reports on the distribution of domestic salt deposits that may be suitable for radioactive waste disposal. The Permian Basin, which includes the Delaware Basin in southeastern New Mexico and large areas in Kansas, west Texas, and Oklahoma, is one of the areas identified in the USGS report.

1963: The research at ORNL is expanded to include a large-scale field program in which simulated waste (irradiated fuel elements), supplemented by electric heaters, is placed in an existing salt mine at Lyons, Kansas. The field program, known as Project Salt Vault, continues until 1967.

1970: In June, the Lyons site is selected by the AEC as a potential location for a radioactive waste repository.

1972: The Lyons site is judged unacceptable due to the area’s uncertain geology/hydrology and previously undiscovered drill holes which could lead to extensive dissolution of salt.

1973: A nation-wide search for a suitable salt site is resumed, resulting in the selection by the AEC, USGS, and ORNL of a portion of the Permian Basin in southeastern New Mexico as best meeting their site selection criteria.

1974: A location 30 miles east of Carlsbad is chosen for exploratory work and extensive field investigations.

On October 11, the U.S. Congress passes the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 (Public Law 93-438). Section 202 of the Act stipulates that the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) shall have “…licensing and related regulatory authority as to facilities used primarily for the receipt and storage of high-level radioactive wastes…”.

1975: A 3,000-foot-deep exploratory borehole, ERDA-6, is drilled at the northwest corner of the originally selected site. The borehole encounters pressurized brine upon intersecting a highly deformed structure at the 2,710-foot level. Consequently, the site is abandoned.

An area approximately 7 miles southwest of the abandoned site is recommended by the USGS for further examination.

New Mexico Governor Apodaca establishes a “Governor’s Advisory Committee on WIPP,” consisting of 10 individuals from New Mexico’s scientific/academic community.

1976: On December 3, the federal Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), the U.S. Department of Energy’s predecessor agency, files an application with the U.S. Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for the withdrawal of 17,200 acres of land in Eddy County for the WIPP Project. The application effectively segregates the identified lands from public entry for a period of two years from the date of its noticing. [Federal Register, Vol. 41, No. 243, p. 54994, December 16, 1976]

Detailed site characterization and engineering design programs are initiated and continue for several years. Results of these studies through late 1978 are reported in the Geological Characterization Report (Powers et al., 1978).

1977: In November, ERDA notifies the NRC of its intention to request a license to construct and operate a radioactive waste repository in New Mexico.

1978: On October 13, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) files an application with the BLM for the withdrawal of 17,200 acres of land in Eddy County, New Mexico, for the WIPP Project. The application effectively continues an earlier segregation of the same identified lands from public entry for a period of two years from the date of its noticing. [Federal Register, Vol. 43, No. 221, p. 53063, November 15, 1978]

The Environmental Evaluation Group (EEG) is established late in this year to provide a full-time, independent technical assessment of the WIPP Project. Although funded entirely by the DOE through Cooperative Agreement No. DE-AC04-79AL10752, the EEG is made a part of the Environmental Improvement Division of the N.M. Health and Environment Department.

1979: During the First Session of the 34th New Mexico State Legislature, a new law is enacted establishing the interim legislative Radioactive and Hazardous Materials Committee and the Radioactive Waste Consultation Task Force, an executive-branch group of three Cabinet secretaries. [Laws of 1979, Chapter 380; Section 74-4A-2 New Mexico Statutes Annotated 1978]

In April, DOE issues its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) on WIPP, which clearly defines the project as a combination military/commercial nuclear waste repository. The following month, however, the House Armed Services Committee of the U.S. Congress moves to cut off funding for the WIPP, citing as the reason DOE’s expansion of the project to a fully licensed (by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission), commercial facility.

As a consequence of the House Armed Services Committee threat to cut off funding for WIPP, the DOE withdraws its plans for a combined commercial/defense repository and retreats to its original proposal to limit the project to an unlicensed, research and development facility for the storage of defense transuranic (TRU) wastes and some limited, high-level waste experiments.

On December 29, the U.S. Congress approves the Department of Energy National Security and Military Applications of Nuclear Energy Authorization Act of 1980 (Public Law 96-164). Section 213(a) of the Act authorizes WIPP “…for the express purpose of providing a research and development facility to demonstrate the safe disposal of radioactive wastes resulting from defense activities and programs of the United States exempted from regulation by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.” The Act also directs the DOE Secretary to enter into a written “consultation and cooperation agreement” with the State of New Mexico by September 30, 1980.

1980: On January 17-18, the EEG convenes a group of 35 scientists and other interested parties to address unresolved geotechnical issues on WIPP. A complementary geological field trip to the WIPP site, hosted by the EEG, occurs in June.

Negotiations on a consultation and cooperation agreement are initiated in early spring and continue through August, when New Mexico Attorney General Jeff Bingaman declares the draft agreement legally deficient in protecting the State’s rights.

In October, the DOE issues its Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) on WIPP, anticipating that revision of the document will resolve deficiencies cited by New Mexico Governor King in the State’s response to the draft EIS. [U.S. Department of Energy, Final Environmental Impact Statement, Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, DOE/EIS-0026, October 1980]

On November 7, the DOE files an application with the BLM for the withdrawal of 8,960 acres of federal land for the purpose of conducting a Site and Preliminary Design Validation (SPDV) program at the WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 45, No. 196, p. 75768, November 17, 1980]

1981: Although State concerns regarding the FEIS are given only cursory attention, the DOE issues in late January its “Record of Decision” to proceed with WIPP construction. [Federal Register, Vol. 46, No. 18, p. 9162, January 28, 1981]

On May 14, New Mexico Attorney General Bingaman files suit in U.S. District Court (Albuquerque) against the DOE and the Interior Department, alleging violations of federal and State law in connection with the continuing development of WIPP. [Civil Action No. 81-0363 JB]

On July 1, U.S. District Judge Juan G. Burciaga issues a federal court Order, which provides New Mexico a meaningful role in the decision-making process for the WIPP Project. The Order stays all proceedings in the State lawsuit in accordance with a Stipulated Agreement, signed by Attorney General Bingaman, DOE, and the U.S. Interior Department. The Stipulated Agreement requires the DOE perform additional geotechnical studies at the WIPP site and then provide the results to the State for review. It also requires DOE and the State to reach a negotiated settlement on certain State “off-site concerns” (e.g., emergency response, highway upgrading, transportation monitoring, accident liability).

Attached as an appendix to the Stipulated Agreement is a fully executed Consultation and Cooperation Agreement, signed by Governor Bruce King and DOE Secretary James Edwards on the same day (July 1, 1981). The “C & C Agreement,” as it has become known, provides for the timely and open exchange of information about WIPP. Significantly, the Agreement also provides New Mexico a mechanism for conflict resolution on matters “…relating to the public health, safety or welfare of the citizens of the State.”

1980: On July 14, DOE initiates drilling of a 12-foot-diameter exploratory shaft at the WIPP site. This first WIPP shaft reaches a total depth of 2,305 feet on October 24, 1981.

1981: At EEG’s urging, the DOE starts deepening a previously drilled borehole (WIPP-12) into the Castile Formation. Located north of the site, WIPP-12 had been drilled to a depth of 2,737 feet in 1978.

On November 22, the DOE strikes a large, highly pressurized brine reservoir in WIPP-12 at a depth of 2,900 feet, producing 350 gallons per minute of brine at the surface. Following an extensive hydrological and geological evaluation, and an EEG recommendation to relocate the TRU waste storage area away from WIPP-12, the DOE redesigns the proposed repository with the TRU waste area relocated approximately 6,000 feet south of its original location.

On December 22, the DOE initiates drilling of a 6-foot-diameter ventilation shaft at the site. This second WIPP shaft reaches a total depth of 2,203 feet on February 22, 1982.

1982: On March 30, 1982, the BLM issues Public Land Order 6232, withdrawing 8,960 acres of federal land (and 1,280 acres of State trust land, if acquired by the federal government) for the purpose of conducting the SPDV program at WIPP. This administrative withdrawal is effective for an 8-year period, March 30, 1982-1990. [Federal Register, Vol. 47, No. 61, p. 13340, March 30, 1982]

In October, underground excavation of the repository begins. Salt is transported to the surface via the exploratory shaft (i.e., the Construction and Salt Handling shaft).

On December 28, the DOE and New Mexico enter into the Supplemental Stipulated Agreement Resolving Certain State Off-site Concerns over WIPP, as required by the July 1, 1981 Stipulated Agreement. Among other provisions, the 1982 Agreement commits DOE to seeking a special Congressional appropriation for upgrading selected non-Interstate WIPP routes in New Mexico. It also clarifies that DOE is liable for any WIPP-related accidents at or en route to the site. The Agreement is signed by Governor Bruce King, Attorney General Bingaman, N.M. Radioactive Waste Task Force Chairman George Goldstein, and Joseph Canepa, Special Assistant Attorney General and primary negotiator of the Agreement.

1983: On January 7, President Reagan signs into law the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 (Public Law 97-425). This Act establishes for the first time a national policy for the safe storage and permanent disposal of spent fuel and high-level radioactive wastes.

On January 17, the DOE files an application with the BLM for the withdrawal of 8,960 of federal land (and 1,280 acres of State land, if acquired by the federal government) for the purpose of constructing WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 48, No. 19, p. 3878, January 27, 1983]

In late March, the DOE completes its SPDV program and issues a report entitled “Summary of the Results of the Evaluation of the WIPP Site and Preliminary Design Validation Program” (WIPP-DOE-161). The State is given 60 days to review and comment.

On May 31, the State delivers its comments on the WIPP-DOE-161 report, citing various unresolved issues (e.g., uncertainties about federal liability under the Price-Anderson Act, compensation for the loss of mineral revenues, etc.). The EEG concludes in its comments that based on existing evidence “…the Los Medanos site for the WIPP project has been characterized in sufficient detail to warrant confidence in the validation of the site for the permanent emplacement of approximately 6 million cubic feet of defense transuranic waste.” The EEG also recommends that several additional studies be conducted to resolve outstanding geotechnical issues. [EEG, “Evaluation of the Suitability of the WIPP Site,” Report EEG-23, May 1983]

On June 29, the BLM issues Public Land Order 6403, withdrawing 8,960 acres of federal land (and 1,280 acres of State trust land, if acquired by the federal government) for the construction of full facilities at the WIPP site. This administrative withdrawal is effective for an 8-year period, June 29, 1983-1991. However, the withdrawal order prohibits “…use or occupancy of the lands hereby withdrawn for the transportation, storage, or burial of any radioactive materials…”. [Federal Register, Vol. 48, No. 130, p. 31038, July 6, 1983]

On July 1, the DOE announces its decision to proceed with full facility construction of the WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 48, No. 128, p. 30427, July 1, 1983]

In August, the EEG reports on the potential for hydrogen gas explosions during transportation of high-curie content contact-handled transuranic (CH-TRU) wastes. [EEG, “Potential Problems from Shipment of High-Curie Content CH-TRU Wastes to WIPP,” Report EEG-24, August 1983]

On September 23, the DOE initiates drilling of a 14-foot-diameter exhaust shaft. This third WIPP shaft reaches a total depth of approximately 2,200 feet on November 22, 1983.

1984: In November, the State and DOE execute the “First Modification to the 1981 Consultation and Cooperation Agreement.” Among other provisions, it requires the DOE to comply with “…all applicable state, federal and local standards, regulations and laws, including any applicable regulations or standards promulgated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).” The modification is signed by Joseph Goldberg, Chairman, N.M. Radioactive Waste Consultation Task Force, and Raymond G. Romatowski, Manager of DOE’s Albuquerque Operations Office (DOE-AL), on November 30.

1985: On April 30, President Reagan advises DOE Secretary John S. Herrington he finds no basis to conclude a defense-only repository is required for the disposal of defense high-level wastes (DHLW). The DOE is therefore directed to proceed with arrangements for disposal of DHLW in civilian repositories in conformance with the presumption of the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982.

On July 29, the EEG notifies DOE that the single-contained, vented rectangular TRUPACT-I, the transportation packaging container intended for shipping contact-handled transuranic wastes to WIPP, is unacceptable for use in New Mexico.

In September, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) promulgates its “Environmental Radiation Protection Standards for Management and Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel, High-Level and Transuranic Radioactive Wastes.” [Federal Register, Vol. 50, No. 182, p. 38066, September 19, 1985] These standards, applicable to the WIPP Project, are subsequently codified in Part 191 of Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (40 CFR 191).

1986: In mid-May, the DOE informs the State of New Mexico that the TRUPACT-I is being redesigned to meet the applicable NRC regulations by incorporating double containment and eliminating the venting feature.

On May 28, President Reagan approves DOE’s recommendation of three sites for detailed characterization as this nation’s first defense/commercial high-level waste repository. These sites include: 1) Deaf Smith County, Texas (bedded salt); 2) Hanford, Washington (basalt); and 3) Yucca Mountain, Nevada (tuff).

In July, the EPA clarifies that the hazardous constituents of radioactive mixed wastes are subject to regulation under Subtitle C of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 (RCRA). [Federal Register, Vol. 51, No. 128, p. 24504, July 3, 1986] This EPA interpretive notice impacts the WIPP Project in that a majority of the wastes destined for WIPP are radioactive mixed wastes and therefore subject to applicable RCRA regulations.

1987: In early May, the DOE confirms and further clarifies EPA’s July 3, 1986, interpretive notice, stating “…all DOE radioactive waste which is hazardous under RCRA will be subject to regulation under both RCRA and the AEA (Atomic Energy Act of 1954).” [Federal Register, Vol. 52, No. 84, p. 15937, May 1, 1987]

In June, the DOE announces that a request for a competitive procurement will shortly be issued for the design and fabrication of a transportation packaging container for use in shipping CH-TRU wastes to WIPP. Later in the year, the DOE selects a new right-circular-cylinder design with unvented double containment.

On July 17, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First District (Boston) vacates and remands to the EPA for reconsideration Subpart B of its “Environmental Radiation Protection Standards for Management and Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel, High-Level, and Transuranic Radioactive Waste,” 40 CFR Part 191. This action, deciding a legal challenge to the EPA standards by the Natural Resources Defense Council and others, impacts WIPP in that there are now no repository standards applicable to the project.

In early August, the State and DOE execute the “Second Modification to the Consultation and Cooperation Agreement.” It requires the DOE to comply with “…all applicable regulations of the U.S. Department of Transportation and any applicable corresponding regulations of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).” The agreement also states: “All waste shipped to WIPP will be shipped in packages which the NRC has certified for use.” Another key provision requires DOE to continue its performance assessment planning “…as though EPA’s 1985 repository disposal standards) remain applicable.” The modification is signed by New Mexico Governor Garrey Carruthers and Attorney General Hal Stratton and by Raymond G. Romatowski, DOE-AL Manager, and DOE-AL Chief Counsel James Stout on August 4, 1987.

A separate agreement, which amends the 1982 Supplemental Stipulated Agreement and relates to funding for WIPP by-passes and relief routes in New Mexico, is also executed on August 4.

On December 22, President Reagan signs into law the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 1987 (Public Law 100-203). This Act provides the defense/commercial high-level waste program dramatic new directions, prohibiting further study of the Washington and Texas candidate repository sites while focusing all efforts on the Yucca Mountain site. The elimination of the bedded salt site in Deaf Smith County, Texas, impacts the mission of the WIPP Project in that the proposed defense high-level waste experiments at the New Mexico repository now have no purpose.

1988: On May 1, the DOE initiates drilling of a second ventilation shaft after reevaluating a 1981 decision to eliminate it as a cost-saving measure. This shaft (the 4th and final WIPP shaft) is completed on April 17, 1989.

1988: On May 3, the BLM issues to the State of New Mexico a land exchange conveyance document. The document conveys to New Mexico 2,519.43 acres of federal land in Eddy County (both surface and mineral estate) in exchange for 1,280 acres of State trust lands (both surface and mineral estate) located within the WIPP withdrawal area. All acreage (i.e., ~10,240 acres) at the WIPP site is now under federal control and administered by BLM. [Federal Register, Vol. 53, No. 115, p. 22391, June 15, 1988]

In June, DOE and New Mexico execute a Cooperative Agreement, No. DE-FC04-88AL53813, entitled “WIPP Enhancement of the State of New Mexico’s Emergency Response Capability.” The Agreement is the funding mechanism by which DOE will meet its commitments as specified in the 1982 Supplemental Stipulated Agreement between the two parties.

On September 13, the DOE announces WIPP will not open as scheduled in early October. Shortly thereafter, the New Mexico Congressional delegation declares all WIPP land withdrawal legislation “dead” for the current session.

On September 29, President Reagan signs into law the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1989 (Public Law 100-456). Section 1433 of the Act assigns the Environmental Evaluation Group (EEG) to the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology and provides for continued funding from DOE through Cooperative Agreement No. DE-AC04-89AL58309.

On October 19, Idaho Governor Andrus imposes a ban on all out-of-state shipments of radioactive wastes to the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory (INEL) due to delays in the scheduled opening of WIPP. Two ATMX railcars of wastes are sent back to the Rocky Flats Plant near Denver, Colorado.

On December 16, Governors Andrus, Carruthers, and Romer (Colorado) meet with DOE Deputy Secretary Joseph Salgado in Salt Lake City to discuss the WIPP Project and options to avert a shutdown of the Rocky Flats Plant, which is rapidly approaching its mixed waste storage capacity limit imposed by the State of Colorado. The DOE agrees to pursue two parallel paths regarding WIPP land withdrawal: administrative and legislative; it also agrees to look at “interim storage” options for Rocky Flats wastes.

1989: On January 19, DOE files an application with BLM for the withdrawal of 10,240 acres of federal land. The application is noticed in the Federal Register of April 19, 1989.

On February 23, Governor Andrus lifts his ban on radioactive waste shipments from Rocky Flats, allowing two ATMX railcars of waste per month to move to INEL for a six-month period. If WIPP is not open by September 1, Andrus states he will reimpose his ban.

In early March, the DOE submits to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) a “No-Migration Variance Petition.” If granted, this petition would provide the DOE a variance (or waiver) from the land disposal restrictions contained in the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and corresponding regulations.

In mid-April, the DOE issues its Draft Supplement Environmental Impact Statement (DSEIS) on WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 54, No. 76, p. 16350, April 21, 1989]

On April 26, the DOE issues its 5-year Test Plan, entitled “Draft Plan for the WIPP Test Phase: Performance Assessment and Operations Demonstration,” DOE/WIPP-89-011, April 1989. An amendment to the Plan is issued on June 16; and a “Draft Final” version of the Plan is issued in December 1989.

On June 27, DOE Secretary Watkins announces an indefinite delay in the opening of the WIPP. He emphatically states “…WIPP will only open when I deem it safe and other key non-DOE reviewers are satisfied.”

In an August 21 letter to DOE Secretary Watkins, Governor Andrus announces his intention to immediately halt all further shipments of radioactive wastes to INEL.

On August 29, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) issues a “Certificate of Compliance” for the TRUPACT-II, the transportation packaging container to be used for shipping contact-handled transuranic (CH-TRU) wastes to the repository.

In October, the DOE issues its “Draft Decision Plan on WIPP.” This Plan outlines the process for reaching the DOE Secretary’s decision point on WIPP’s readiness for initial receipt of waste. It also identifies key prerequisites and activities to be completed prior to the Secretary’s decision.

Revision 1 to the Draft Decision Plan, issued in November, identifies July 1, 1990, as the “earliest possible opening date for WIPP” due to the various prerequisites and activities that must be completed—-many of which are beyond DOE’s control (e.g., land withdrawal, EPA’s decision on “No-Migration Variance Petition”).

1990: In late January, the DOE issues its Final Supplement Environmental Impact Statement (FSEIS) on WIPP. [U.S. Department of Energy, Final Supplement Environmental Impact Statement, Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, DOE/EIS-0026-FS, January 1990]

In April, EPA issues its proposed regulation granting a conditional no-migration variance for WIPP mixed wastes, as allowed under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulations. [Federal Register, Vol. 55, No. 67, p. 13068, April 6, 1990]

In mid-April, the DOE issues its “WIPP Test Phase Plan: Performance Assessment,” DOE/WIPP 89-011, Revision 0. This document provides DOE’s plans for conducting a number of studies and experiments with TRU wastes during a five-year Test Phase at the WIPP facility. Approximately 4,500 drums of wastes, or about 0.5% of WIPP’s design capacity, are proposed to be brought to the repository for conducting gas generation experiments.

On June 14, the DOE approves the Final Safety Analysis Report (FSAR), a document which identifies and analyzes the risks of potential hazards associated with WIPP operations (fires, radiation releases) as well as naturally occurring hazards that may affect the facility (tornadoes, earthquakes). The FSAR also outlines measures to reduce risks and control or mitigate the hazards. Not addressed in the present-scope FSAR are activities proposed for the WIPP five-year Test Phase; these activities are to be analyzed and documented in Addenda to the FSAR.

Also in mid-June, the DOE announces Secretary Watkins’ approval of a “Record of Decision” (ROD) on the WIPP Final Supplement Environmental Impact Statement. The ROD states DOE’s intention to proceed with a phased approach to the development of WIPP. Full operation of the WIPP is to be preceded by a Test Phase of approximately five years during which time certain experiments with limited waste volumes would be carried out. However, the ROD notes that “…a decision on whether to proceed with an Operations Demonstration as part of the Test Phase should not be made until a high level of confidence in complying with the EPA disposal standards has been achieved and a determination is made that additional operational experience with waste is required.” Also noted is the fact that a second WIPP Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) will be prepared prior to a decision on whether to proceed from the Test Phase to the Disposal Phase. [Federal Register, Vol. 55, No. 121, p. 25689, June 22, 1990]

Concurrent with the issuance of the Record of Decision, DOE Secretary Watkins announces that January 1991 is the earliest possible date for the initial receipt of wastes at WIPP.

On June 30, the DOE reaches agreement with a New Mexico subsidiary of International Minerals and Chemical Corporation (IMC Fertilizer, Inc.) regarding the purchase of its leasehold interests in a federal potash lease. The purchase agreement, totalling $25.8 million, settles the last of the existing mineral leases within the WIPP withdrawal area.

Effective July 25, the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) is authorized by EPA to regulate radioactive mixed wastes in New Mexico in accordance with its approved program. This State regulatory authority extends to TRU mixed wastes destined for WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 55, No. 133, p. 28397, July 11, 1990]

As a cooperating agency on the WIPP Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), BLM issues in mid-September a “Record of Decision” to implement the Proposed Action in the SEIS by recommending that the Secretary of the Interior approve DOE’s request for an amended administrative withdrawal for the WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 55, No. 182, p. 38586, September 19, 1990; Vol. 55, No. 222, p. 47926, November 16, 1990]

On October 12, the N.M. Environmental Improvement Board (EIB) designates a “preferred route,” as that term is defined in 49 CFR 397.101, from the State’s northern border to the WIPP repository. The EIB designation also requires the use of by-passes and beltways around communities, when they are available.

In late October, the EPA issues a conditional no-migration determination for the WIPP facility. As a result of this determination, the DOE may place a limited amount (i.e., up to 8,500 drums or 1% of the repository’s total design capacity) of untreated hazardous waste subject to the land disposal restrictions of the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) in the WIPP for the purposes of testing and experimentation. [Federal Register, p. 47700, November 14, 1990]

1991: In late January, the BLM issues another WIPP “Record of Decision” (ROD) to adopt the Final SEIS and implement the Proposed Action by approving the public land order modifying the administrative withdrawal for the WIPP Project. [Federal Register, Vol. 56, No. 18, p. 3114, January 28, 1991]

Concurrent with the preceding BLM action, the U.S. Interior Department issues Public Land Order No. 6826, which modifies an earlier WIPP administrative land withdrawal order (Public Land Order No. 6403) as follows: (1) Expansion of the Order’s purpose to include the conduct of a Test Phase at WIPP using retrievable, transuranic radioactive waste; (2) Extension of the term of the withdrawal for six years, through June 29, 1997; and (3) Expansion of the DOE’s exclusive use area, where WIPP surface facilities are located, from 640 acres to 1,453.90 acres. [Federal Register, Vol. 56, No. 18, p. 3038, January 28, 1991; and Vol. 56, No. 29, p. 5731, February 12, 1991]

On March 6, the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives approved a resolution by Congressman Bill Richardson (D-NM) that is aimed at nullifying the federal Interior Department’s Public Land Order No. 6826. The resolution invokes a provision found in Section 204(e) of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 and corresponding regulations.

In early April, the U.S. Interior Department proposes to modify WIPP Public Land Order 6826 for the purposes of prohibiting until June 30, 1991, the transportation or emplacement of any radioactive waste within the WIPP. The action is proposed to accommodate concerns raised in the above-referenced House resolution about environment, safety, and public health matters. [Federal Register, Vol. 56, No. 62, p. 13335, April 1, 1991]

Effective April 4, the New Mexico State Legislature transfers responsibility for the designation of highway routes for the transport of radioactive materials from the N.M. Environmental Improvement Board (EIB) to the N.M. State Highway Commission. [Laws of 1991, Chapter 204, Section 1; 74-4A-1 NMSA 1978] This action also nullifies and voids EIB’s 1990 WIPP route designation.

On June 26, the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives passes a WIPP land withdrawal bill, H.R. 2637. Two other committees in the House (Energy and Commerce, Armed Services) and one in the Senate (Energy and Natural Resources) also have jurisdiction over the legislation.

On July 1, the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) notifies DOE of its preliminary determination that WIPP may not qualify for “interim status” under the State’s Hazardous Waste Act (HWA). The HWA is the state analog to RCRA, and NMED enforces the HWA and its corresponding regulations in New Mexico.

In August, the N.M. State Highway Commission designates new WIPP routes in New Mexico after a comprehensive comparative analysis of alternative routes and a series of public hearings. The N.M. State Highway and Transportation Department (SHTD) incorporates the WIPP route designation in its SHTD Rule No. 91-3 and provides subsequent notice of the designation to the U.S. Department of Transportation pursuant to 49 CFR Part 397.101.

In late September, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rules that the ban on out-of-state radioactive waste shipments imposed by Idaho Governor Andrus is illegal. The Court’s decision may have implications on other states’ attempts to stop such shipments. On October 5, a shipment of high-level nuclear waste from the inactive Fort St. Vrain reactor in Colorado crosses the state’s border en route to the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory.

On October 3, DOE Secretary Watkins notifies U.S. Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan, Jr., that WIPP is ready to begin the Test Phase. Similarly, the State of New Mexico is notified that the first shipment of waste may reach the WIPP site by October 10. The Watkins letter to Secretary Lujan certifies that “…all environmental permitting requirements have been met by DOE for WIPP.” This certification is required under Public Land Order (PLO) 6403, as modified by PLO 6826, before the Interior Department may issue a “Notice to Proceed” to the DOE. This same day, Mr. David O’Neal, Assistant Secretary of the Interior, issues the preceding notice, which provides DOE authorization to transport and emplace wastes at the WIPP site under the above-referenced Public Land Orders (i.e., the so-called “administrative” withdrawal). [Federal Register, Vol. 56, No. 196, p. 50923, October 9, 1991]

On October 9, New Mexico Attorney General Tom Udall files a lawsuit against DOE and the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) to stop the threatened shipment of wastes to WIPP under the administrative withdrawal. [Civil Action No. 91-2527] The lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, alleges violations of the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and the Administrative Procedure Act. The State of Texas, three Congressmen, and four environmental groups sign on as plaintiff-intervenors in the case. The 1,000-page filing by the Attorney General provides documentation in support of a motion for both a Temporary Restraining Order and a Preliminary Injunction. A hearing date is set for November 15.

On October 16, the Energy and Natural Resources Committee of the U.S. Senate substantively amends and reports out its version of WIPP land withdrawal legislation, S. 1671. This bill is unanimously passed by the full Senate on November 5.

In early November, the same four environmental groups participating as plaintiff-intervenors in the State of New Mexico’s Civil Action No. 91-2527 file a separate WIPP lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. [Civil Action No. 91-2929] This lawsuit, which alleges that WIPP lacks “interim status” under RCRA, is consolidated with the State’s suit in December.

On November 20, the Energy and Commerce Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives passes its version of WIPP land withdrawal legislation (H.R. 2637). The following day, the House Armed Services Committee passes a separate version of the same bill. All three House committees with jurisdiction over the WIPP legislation have now acted and must reconcile their differences.

On November 26, U.S. District Court Judge John Garrett Penn issues an Order, along with a corresponding explanatory memorandum, granting the State’s motion for a preliminary injunction. [Civil Action 91-2527] The Order directs DOE to cease all activities relating to the WIPP Test Phase insofar as they involve the introduction or transportation of TRU waste into New Mexico.

1992: On January 31, Judge Penn issues an Order that imposes a permanent injunction prohibiting the transport or disposal of any TRU waste at WIPP; it also grants two separate motions for summary judgment in the consolidated WIPP lawsuits.

In the first of the consolidated suits, State of New Mexico v. Watkins (Civil Action No. 91-2527), the issue was whether the U.S. Interior Department had violated the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) by issuing a WIPP administrative withdrawal order. Judge Penn granted the plaintiff-intervenor’s motion for summary judgment on the basis that “…the Secretary of Interior cannot extend a withdrawal of WIPP for a new purpose not required by the purpose of the original withdrawal.” Interior’s original Public Land Order No. 6403 withdrew federal lands at the WIPP site for “construction” of the facility and prohibited the transport or emplacement of any radioactive waste at WIPP. However, the DOE’s proposed modification to the original withdrawal was for conduct of a Test Phase requiring the use of radioactive waste—-clearly a “new” purpose.

In Environmental Defense Fund v. Watkins (Civil Action No. 91-2929), the Court had to decide whether WIPP has “interim status” under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) so that DOE may proceed with its Test Phase. On this issue, Judge Penn granted EDF’s motion for summary judgment on the basis that “…the WIPP facility could never gain interim status because it was built after the wastes it will manage became regulated by RCRA.” Judge Penn identified the operative RCRA “trigger” date as November 19, 1980 — the date when the federal EPA’s initial hazardous waste management program regulations became effective. DOE had conceded in its filings that WIPP was not in existence on or before that date.

In March, DOE appeals Judge Penn’s ruling of January 31, 1992. Oral arguments are scheduled in the U.S. Court of Appeals (D.C. Circuit) for May 15.

On June 18, the House Rules Committee of the U.S. Congress agrees to bring to the House floor the Energy and Commerce version of the WIPP legislation. However, two major changes are made to that version: (1) the land withdrawal would be permanent; and (2) radioactive wastes cannot be emplaced at WIPP for Test Phase experiments until EPA issues final repository disposal standards (40 CFR Part 191).

On July 10, the federal Appeals Court (D.C. Circuit) issues its decision on DOE’s appeal of the U.S. District Court’s ruling in the WIPP consolidated lawsuits. [Civil Action Nos. 91-5387 and 92-5044] The decision reversed the earlier ruling that WIPP was not eligible for interim status under RCRA. Hence, WIPP may qualify for interim status, but the Appeals Court deferred that decision to the U.S. District Court. On the second issue, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the District Court’s decision that Interior Secretary Lujan exceeded his authority under FLPMA in approving WIPP Public Land Order 6826, issued January 22, 1991. Consequently, the permanent injunction prohibiting any transportation or disposal of waste at WIPP is left in place.

1992: On July 21, H.R. 2637 (WIPP land withdrawal legislation) is debated on the U.S. House floor, amended, and passed by the full House on a vote of 382-10. An amendment by Congressman Bill Richardson (D-New Mexico) to prohibit the receipt of wastes until DOE demonstrates compliance with final EPA repository disposal standards fails. The provisions of the Senate and House WIPP bills must now be reconciled through a conference committee. Consequently, seven (7) conferees are appointed by the Senate and twenty-four (24) by the House.

On August 5, the 31-member Conference Committee appointed to reconcile differences between the competing versions of WIPP land withdrawal legislation meets to go over the ground rules and identify key issues for resolution.

On October 6, U.S. Senate and House conferees agree on a Conference Report regarding WIPP land withdrawal legislation. The report is subsequently adopted by voice vote in both the House (on October 6) and the Senate (on October 8). The bill is sent to the President for signature.

On October 30, President Bush signs the WIPP legislation into law. Among its key provisions, the WIPP Land Withdrawal Act (Public Law 102-579) establishes prerequisites for initial receipt and permanent disposal of TRU wastes at WIPP. The Act also specifies the statutory, regulatory and other requirements and restrictions applicable to the WIPP facility and its operations. Significantly, the EPA is designated as a primary independent regulator at WIPP with authority to determine whether the repository is suitable as a long-term disposal facility.

At year-end, DOE issues a key document entitled “Gas Generation and Source-Term Programs: Technical Needs Assessment for the WIPP Test Phase.” [DOE/WPIO/001-92, Revision 0, December 1992]

1993: In early February, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issues proposed regulations, codified at 40 CFR Part 191, entitled “Environmental Radiation Protection Standards for the Management and Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel, High-Level and Transuranic Radioactive Wastes.” [Federal Register, Vol. 58, No. 26, p. 7924, February 10, 1993] The next day, EPA issues an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on criteria for its certification of WIPP’s compliance with the above-referenced radiation protection standards. [Federal Register, Vol. 58, No. 27, p. 8029, February 11, 1993] Both the standards and criteria will be used to determine WIPP’s suitability as a disposal facility.

1993: On March 25, DOE issues two key WIPP documents: 1) a “Test Phase Plan” [DOE/WIPP 89-011, Revision 1, March 1993]; and 2) a “Waste Retrieval Plan” [DOE/WIPP 89-022, Revision 1, March 1993]. Submission of these plans to EPA for review, along with public notice of their availability, are required under the WIPP Land Withdrawal Act. [Federal Register, Vol. 58, No. 55, p. 15845, March 24, 1993]

On October 21, DOE announces that tests using radioactive waste will be conducted in laboratories rather than underground at the WIPP site. Various organizations had criticized the previously planned bin and alcove tests in that they would not provide information directly relevant to a certification of compliance with the applicable disposal standards.

On December 9, DOE creates a new area office in Carlsbad, New Mexico (i.e., Carlsbad Area Office), which combines all functions of the WIPP Project Integration Office in Albuquerque and the WIPP Project Site Office in Carlsbad. Mr. George Dials is selected as the first DOE-CAO Manager.

In mid-December, the EPA issues a Final Rule that amends its regulations codified at 40 CFR Part 191 and entitled “Environmental Radiation Protection Standards for the Management and Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel, High-Level and Transuranic Radioactive Wastes.” [Federal Register, Vol. 58, No. 242, p. 66398, December 20, 1993] The amendments become effective January 19, 1994, and provides DOE a definitive set of disposal regulations with which WIPP must comply.

1994: In a letter to Judith Espinosa (Cabinet Secretary, New Mexico Environment Department) dated February 14, 1994, George Dials (WIPP Project Manager, DOE-CAO) states that “…DOE has no plans or intentions of disposing of any wastes (neither hazardous, radioactive, nor mixed) in the WIPP prior to receipt of a RCRA Part B Disposal Phase permit.” DOE later reverses its above-stated position regarding the receipt of non-mixed waste at WIPP prior to issuance of a RCRA Part B Disposal Phase permit from the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED).

In April, DOE-CAO develops a “Disposal Decision Plan” that identifies key milestones and time lines for a variety of WIPP activities, including stakeholder interactions and regulatory compliance for commencement of disposal operations.

1995: In late January, EPA issues a Proposed Rule establishing criteria for certifying whether WIPP complies with the disposal standards set forth in 40 CFR Part 191. [Federal Register, Vol. 60, No. 19, p. 5766, January 30, 1995]

1995: On May 17, H.R. 1663 is introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives by Congressman Joe Skeen (R-New Mexico), with co-sponsorship by Dan Schaefer (R-Colorado) and Mike Crapo (R-Idaho). If enacted, this legislation would amend the 1992 WIPP Land Withdrawal Act (Public Law 102-579).

On May 26, DOE-CAO submits a 13-volume Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Part B permit application [DOE/WIPP 91-005, Rev. 6] to the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED).

On July 25, NMED determines DOE’s RCRA Part B application for WIPP is “administratively” complete. Over the next year, DOE provides additional documentation to NMED in response to its ongoing review and comments on the application.

On November 8, S. 1402 is introduced in the U.S. Senate by Senator Larry Craig (R-Idaho), with co-sponsorship by J. Bennett Johnston (D-Louisiana) and Dirk Kempthorne (R-Idaho). It is a companion bill to H.R. 1663.

1996: In early February, EPA issues a Final Rule establishing criteria for use in certifying whether WIPP complies with the applicable disposal standards set forth in 40 CFR Part 191 (i.e., WIPP Compliance Criteria). [Federal Register, Vol. 61, No. 28, p. 5224, February 9, 1996] These criteria (i.e., WIPP Compliance Criteria) are codified at 40 CFR Part 194 and become effective April 9, 1996.

On April 8, the New Mexico Attorney General files a petition in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit for review of EPA’s final WIPP Compliance Criteria, 40 CFR Part 194. [Civil Action No. 96-1107] This petition is ultimately consolidated with two other similar petitions filed by: two environmental groups and two individuals [Civil Action No. 96-1108]; and the Texas Attorney General [Civil Action No. 96-1109]. The petitions allege violations by EPA of the WIPP Land Withdrawal Act and the Administrative Procedure Act in promulgating the WIPP criteria.

On June 20, legislation (H.R. 1663, S. 1402) amending the 1992 WIPP Land Withdrawal Act is attached as a “rider” (Amendment #4085) to S. 1745, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997. It passes the full U.S. Senate on a voice vote.

On June 26, NMED determines that DOE’s RCRA Part B permit application is “technically” complete.

On July 10, the full U.S. Senate passes S. 1745 by a vote of 68-31. The Senate incorporates the measure as an amendment to H.R. 3230, the U.S. House of Representatives’ version of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997 and requests a conference with the House.

1996: On July 15, DOE-CAO submits a final No-Migration Variance Petition to the EPA. The petition seeks a variance from the Land Disposal Restrictions of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), as codified in 40 CFR Part 268, in order to dispose of TRU “mixed” waste at WIPP.

On July 30, the House/Senate conferees for H.R. 3230 produce a Conference Report. The report, which includes the WIPP Land Withdrawal Act amendments, is filed in the U.S. House of Representatives. [H. Report 104-724, Title XXXI, Subtitle F, Sections 3181-3191]

On August 1, the full U.S. House of Representatives approves the H.R. 3230 Conference Report on a vote of 285-132.

On September 10, the full U.S. Senate approves the H.R. 3230 Conference Report on a vote of 73-26 and sends it on to the President for signature.

On September 23, President Clinton signs into law the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997 (Public Law 104-201). This law contains amendments to the 1992 WIPP Land Withdrawal Act, most notably a provision exempting WIPP mixed waste from the land disposal restrictions under the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). This RCRA exemption obviates the need for DOE to receive EPA approval under 40 CFR Part 268 of the pending WIPP No-Migration Variance Petition.

1997:

On January 25 a TRUPACT-II transporter struck a cow approximately 40 miles north of Carlsbad, NM. The truck was NOT carrying any waste. There were no injuries to the drivers. The drivers contacted the State Police, who investigated the incident. No citations were issued. However, the State of New Mexico was not notified of the incident until the following morning. Therefore, in the days following the incident, both the State and DOE put in place directives that all incidents from this point forward would follow established notification procedures, regardless of whether or not the vehicle was transporting waste.

In early February, spent nuclear fuel shipments from Los Alamos National Laboratory followed vehicle inspection procedures established for transuranic waste shipments to WIPP. The New Mexico Motor Transportation Division (MTD) inspected all 3 shipments to ensure compliance with CVSA Level VI inspection criteria.

On June 6, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit denies petitions filed by the New Mexico Attorney General and others for review of EPA’s final WIPP Compliance Criteria. In denying the petitions, the Appeals Court judges state: “We have addressed petitioners’ strongest arguments, and find no merit in the others.” The final criteria stand as promulgated.

In September, DOE issues its WIPP Disposal Phase Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (DOE/EIS-0026-FS2, September 1997). The document’s Proposed Action, which is also DOE’s Preferred Alternative, is to continue with the phased development of WIPP by disposing of TRU waste at the repository.

On September 26, NMED rescinds its “technical” completeness determination on the RCRA Part B permit application for WIPP after receiving substantial new material (~10,000+ pages) from DOE.

In late October, the EPA issues a Proposed Rule certifying that WIPP complies with the disposal standards set forth in 40 CFR Part 191. [Federal Register, Vol. 62, No. 210, p. 58792, October 30, 1997] A 120-day public comment period commences, with public hearings scheduled for early 1998. The proposed certification would allow Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) to ship to WIPP transuranic waste from specific LANL waste stream (i.e., site legacy). However, the proposed certification is also subject to several conditions, notably that EPA must approve site-specific waste characterization measures and quality assurance plans before allowing other waste generator sites to transport and dispose of wastes at WIPP.

1998: In mid-January, the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) determines that DOE’s RCRA Part B permit application is “technically” complete.

Also in January, DOE issues a “Record of Decision” (ROD) to dispose of TRU waste at WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 63, No. 15, p. 3624, January 23, 1998] This ROD documents DOE’s decision to implement the Preferred Alternative, as analyzed in the WIPP Disposal Phase Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. Simultaneously, DOE issues a related ROD on where (i.e., at which DOE sites) the Department will prepare and store its TRU waste prior to disposal at WIPP. [Federal Register, Vol. 63, No. 15, p. 3629, January 23, 1998] This ROD is based on analyses in the Final Waste Management Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (DOE/EIS-0200-F, May 1997).

On May 13, EPA announces it is certifying that WIPP will comply with the applicable disposal regulations set forth at Subparts B and C of 40 CFR Part 191. [Federal Register, Vol. 63, No. 95, p. 27354, May 18, 1998] Immediately following the EPA announcement, DOE Secretary Federico Pena notifies Congress that WIPP is ready to begin disposal operations. Also on this same date, DOE petitions the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to lift its 1992 permanent injunction barring the transport or introduction of any TRU waste at WIPP. Subsequently, oral arguments in the case are scheduled for March 12, 1999.

On May 15, the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) issues a draft RCRA Part B permit for the storage and disposal of TRU mixed waste at WIPP. Issuance of the draft permit starts a 90-day public comment period.

On May 21, DOE Secretary Federico Pena notifies the State of New Mexico that it intends to use WIPP to dispose of selected non-mixed TRU waste from Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) prior to the receipt of a RCRA Part B permit from NMED. This reverses DOE’s earlier position that it would not dispose of any TRU waste at WIPP before issuance of a RCRA permit.

On June 11, NMED determines that DOE has failed to adequately characterize the selected LANL waste stream (TA-55-43, Lot 1) to demonstrate it is non-mixed TRU waste. Shortly thereafter, DOE and NMED reach agreement on a schedule and process for making a determination on the LANL waste in question.

On July 16, the New Mexico Attorney General, three environmental groups, and a private citizen file petitions in the U.S. Court of Appeals (D.C.), alleging violations of notice and comment rulemaking and substantive technical errors in EPA’s certification of WIPP. [Civil Action Nos. 98-1322, -1323, -1324] Subsequently, oral arguments in the consolidated cases are scheduled for May 6, 1999.

On July 27, DOE submits a “Confirmatory Sampling and Analysis Plan” to NMED. This plan goes through several revisions and is ultimately approved by NMED on September 24. DOE proceeds to sample and analyze the selected LANL waste stream in accordance with the approved plan.

On November 13, NMED issues a revised draft permit for the storage and disposal of TRU mixed waste at WIPP. Issuance of the revised draft permit starts a 60-day public comment period; a series of public hearings, commencing February 22, 1999, in Santa Fe, are also scheduled.

On November 16, DOE provides the results of its confirmatory sampling and analysis on the selected LANL waste stream to NMED. [U.S. Department of Energy/Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sampling and Analysis Project Validates Acceptable Knowledge on TA-55-43, Lot No. 1, Rev. 0, November 16, 1998]

On December 2, NMED makes a determination that the selected LANL waste stream (TA-55-43, Lot 1) is non-mixed waste.

See What’s New

to find out about recent events

SOURCE: Compiled by Christopher J. Wentz, former Coordinator & Senior Policy Analyst, Radioactive Waste Consultation Task Force, State of New Mexico, February 1999. Additional information can be obtained by contacting Anne deLain W. Clark, former Coordinator of the New Mexico Radioactive Waste Consultation Task Force.